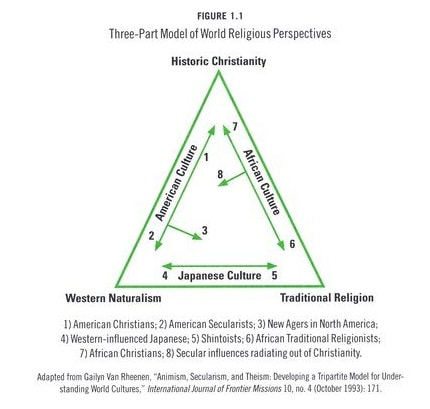

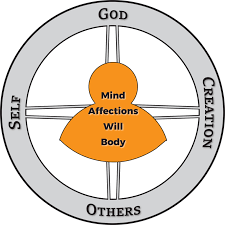

Becoming Whole Review4/16/2021 This book tries to marry theology and economics in addressing poverty. The authors want to bring spiritual brokenness or “deformation” into the conversation about why people are materially poor and whether improving their material circumstances should be our highest goal. This book is about the full Gospel story: Creation, Fall, Redemption, and Restoration. It brings Biblical theology to bear on all kinds of human activity. One way to read the authors’ message is that we (wealthy western Christians) don’t really understand flourishing very well, even for ourselves. The problem is not even that we aren’t good at helping other people become wealthy, it’s that we don’t rightly understand the role of wealth in human flourishing in general. Because they correct not just the methods of poverty alleviation but the goals as well, the authors jump back and forth between discussing what we need to understand in order to help poor people, and what we need to be doing and believing to help ourselves become whole. They offer several schematizations of how historic Christianity has been corrupted or distorted by two alternative views of the world: Traditional Religion and Western Naturalism. They draw a triangle with Historic Christianity, Traditional Religion, and Western Naturalism as the three points. Many western European countries fall between Historic Christianity and Western Naturalism while most developing countries, especially in Africa, fall between Historic Christianity and Traditional Religion. Although the authors are no fans of Traditional Religion, they spend most of their time criticizing western capitalist cultures that fall between the other two points resulting in what they call Evangelical Gnosticism. This gnosticism involves taking ideas about the spirit or soul from Christianity and combining them with ideas about wealth, success, and material flourishing from Naturalism. Division between the material and the spiritual results - leading to too little or to too much focus on the soul or on one’s material circumstances. For example, many evangelical Christians have the view that salvation is only about saving our souls from Hell so that we can live as disembodied spirits worshipping God forever in heaven after we die. This emphasis on the spiritual after-life leads to a neglect or misunderstanding of how we ought to live in this world. We believe the right things about God, but otherwise pursue flourishing the way those around us do with higher-paying jobs, more savings, bigger houses, better vacations, cooler gadgets and toys, etc. On the other hand, this Evangelical Gnosticism can lead to hyper-spiritualization. The only thing that matters is the spiritual and getting as many people saved as possible. This focus leads to personal deformation too because we are soul and body, not just souls. The “American Dream,” Fikkert and Kapic argue, should not be where Christians try to get poor people. Turning poor materialistic religious traditionalists into wealthier materialistic naturalists does not seem like much of a gain in the grand scheme of things. They argue that the more people buy into Western Naturalism, the more they become like “consuming robots” living in relational poverty and internal disorder. The authors connect this, understandably, to our current mental health challenges and the remarkable rise in depression and suicide in wealthy technologically advanced societies. Returning to the main goal of the book, Fikkert and Kapic argue that people are complex and in trying to help them we should consider far more than their external incentives, constraints, and material resources the way an economist might. Instead, we should recognize that people are made up of Mind, Affections, Will, and Body. They have healthy or unhealthy relationships with God, Self, Others, and Creation. When Christian charity or aid focuses on some of these categories but not others, it fails to address the whole person and therefore fails to bring deep human flourishing. Even as someone’s material circumstances improve, they could have worsening relationships with God and with others. Though they can consume more, there may be little improvement in their Mind or their Affections. All the categories highlighted by the authors are connected and true human flourishing results from proper integration of them. The point of Becoming Whole is restoring people to good relationships with God, others, and the world. When you have those relationships right, productivity, wealth, and happiness follow. And you can have good relationships regardless of your material standard of living. So in many ways Fikkert and Kapic are inverting the “normal” approach to poverty: “first, let’s get you to a better standard of living, than we can talk about your emotional, spiritual, relational problems once your physical ‘needs’ are met.” “No,” the authors respond, “let’s understand how your emotional, spiritual, and relational problems are connected to your material poverty. Then we can think about tackling those problems and actually address your material poverty more effectively.” I think the authors are a bit harsh on western civilization and culture at times. But when I look at the frightening statistics on depression, anxiety, lack of family formation or stability, declining church membership, deep political and social polarization, and radicalization happening in the U. S., they are not wrong. Something seems to be terribly amiss, even in many Christian communities. Perhaps we should blame the dominance of Evangelical Gnosticism for warping and impoverishing how we understand ourselves, God, others, and our place in the world. There were two quotes from the book that I found particularly insightful. The first was Carl Henry writing: "The early church didn’t say, ‘Look what the world is coming to!’ They said, ‘Look what has come into the world!’" Christians should be captivated by the reality of their God who came into the world to rescue us from darkness. Jesus saves us not only for the next life, but also for this present life. We have work to do for the kingdom and for spreading Christ’s dominion. Yes, there are problems in the world and societies decline - but that is not the main point of history. I also found a quote from theologian Christopher Wright really helpful in understanding what “institutional” sin means: “We need to be careful here, of course. Some people are very reluctant to speak of ‘structural sin,’ arguing that only people can sin. Sin is a personal choice made by free moral persons. Structures cannot sin in that sense. With that I agree. However, no human being is born into or makes his or her moral choices in the context of a clean sheet. We all live within social frameworks that we did not create. They were there before we arrived and will remain after we are gone, even if individually or as a whole generation we may engineer significant change in them. And those frameworks are the result of other people’s choices and actions over time--all of them riddled with sin. So although structures may not sin in the personal sense, structures do embody myriad personal choices, many of them sinful, that we have come to accept within our cultural patterns….It is not that by living within such structures our sin becomes justifiable or inevitable. We are still responsible persons before God. It does mean that sinful ways of life become normalized, rationalized, rendered plausible and acceptable by reference to the structures and conventions we have created.” (pg. 177-178 Fikkert & Kapic) Wright suggests here that we need to be willing to consider that practices, habits, beliefs, or institutions that we have cannot be perfect this side of heaven and may have some grave flaws or dangerous tendencies that are not in-step with orthodox Christian doctrine and the Gospel.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply.AuthorPaul Mueller is a Senior Research Fellow at AIER, a research fellow and associate director for the Religious Liberty in the States project at the Center for Religion, Culture, and Democracy, and the owner and operator of The Abbey Bed and Breakfast. Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed